JH: I imagine that the Rencontre and the award were very different from the Oscars?

MDdeW: I'd never watched the Oscars on TV and only when I was there did I realise that for the Americans it really is like a religion. That success means everything. I enjoyed the hype. For the Rencontre, I travelled to Droue and of course, I knew I was to receive the prize. The afternoon when Mylène officially declared the award, we'd already talked about the prize.

JH: This all took place on the cinema bus?

MDdeW: Yes, it was wonderful, all inside a converted bus which folds open into a theatre, very comfortable and professional. Mylène made a short speech and handed me the medallion. It bears the inscription "Sois le premier à voir ce que tu vois comme tu le vois," a Robert Bresson quote. I thanked her and my films were shown.

JH: "Be the first to see what you see as you see it." And which of Bresson's films had you seen before the award?

MDdeW: Au Hasard Balthazar was the first film I saw

JH: Like me! It's a seductive introduction.

MDdeW: Yes, but then you see these actors with downcast eyes, so straight away I thought "Hang on". Because I've got a variety of tastes, but I'm particularly fond of the Mike Leigh school that uses quite realistic behaviour, or The Office with Ricky Gervais. So, to have such a stylised acting, I had to enter into the language, and I did, happily. Then I saw Mouchette, Les Anges du Péché and Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, L'Argent, Le Diable Probablement. And since then, I've seen all of the others, except Une Femme Douce.

JH: I'll lend you my copy. It was a big influence on my first film. It's very beautiful, told in flashbacks. Around a woman's suicide.

MDdeW: I'll look forward to seeing it. I was struck by each of the films, in different ways. In fact, I liked Les Anges more than I expected.

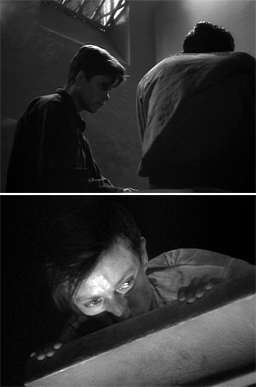

From Un condamné à mort s'est échappé (Robert Bresson, 1956). |

|

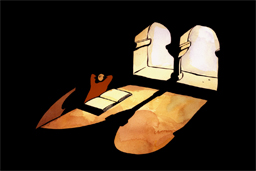

Top: Les Anges du Péché (Robert Bresson, 1943). Bottom: From The Monk and The Fish (Michael Dudok de Wit, 1994). Click it! |

JH: I love Les Anges du Péché. I was thinking about it in relation to your film, The Monk and The Fish. There are some diagonal frames across the cloisters that were similar to Bresson's framing, although your angles are higher!

MDdeW: Yes, of course, he didn't use any high angles...

JH: No, they're all really at eye level.

MDdeW: ...except when the prisoner finally escapes in Condamné à Mort but then that's structured around his viewpoint. In which way was Une Femme Douce a big influence on your first film?

JH: I was influenced by Bresson's overall approach, his tone and pace and I was especially influenced by the intense concentration on doors, hands and transactions in Une Femme Douce. What do you think Bresson saw in your films?

MDdeW: Well, he didn't see my last film, Father and Daughter. Mylène saw Father and Daughter. He'd seen The Monk and The Fish and it's interesting that he liked it because humour is not very present in his films.

JH: No, I was making a list of similarities and differences. And you have music and humour, which are quite clear differences. Bresson had a wonderful sense of humour as a man, although it's less clear in the work. Of course, there's the film within the film in Four Nights, the gangster film and also the artists talking about "action painting" in Balthazar. There's an ironic humour in those scenes. But in general, no, he's not a humorist. And yet The Monk and The Fish is probably the funniest of your films.

MDdeW: If the question is what's the affinity between his work and my work, then there's this striving for purity, I think, which I admire a lot in his work. And simplicity which, in a way, is the same thing. And this is hard to say because it's such an elusive subject, some people suggest that there's this special spiritual quality to his work, that it's not just entertainment. I think this timeless quality is there but it's not pushed in your face. It's more for those who want to see it and that's also true, I hope, in my films. I'm very conscious that my films are entertainment for those who want to see entertainment. Those who want to see more of a finer, spiritual quality in them, that's there too, or at least it is for me. And without preaching, or being linked to a religion in a direct way, Bresson had that. He was very non-judgemental in his films and that adds to their beauty. Even in Les Anges du Péché, which is set in a convent.

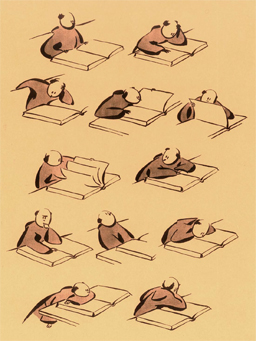

JH: I thought that there were a number of things that bound you together. Thinking just about The Monk and The Fish, there are two quotations in Bresson's Notes on Cinematography that struck me. Bresson quotes Corot, "One must not seek, one must wait." And also, "Empty the pond to get the fish." And of course, these are just about the only two strategies the monk doesn't try. I could imagine Bresson having found your film amusing, as well as profound. Another thing, of course, that you share is painting. Bresson's first love and your films are beautifully realised at the level of illustration, composition and draughtsmanship. Also, what's clear, watching your films in chronological order, is the sense of an artist's evolution.

MDdeW: I should say that Tom Sweep was intended to be one of a series of films, whilst The Monk and The Fish came completely from my heart. When I did that, I thought, well, if it doesn't work, perhaps I'm not supposed to make my own films. And Father and Daughter too, came in the strongest possible way from my own centre. Father and Daughter has had the biggest audience. To my surprise because humour is not very present. It's a serious film.

MDdeW: Yes, Mylène mentioned that too and I think it was one of the reasons she had chosen my work for the Prix. She described her preference for films which have a very personal approach.

JH: There's also an almost documentary aspect to your films. And that's in Bresson too, in a very particular way. For Bresson, the camera and tape recorder captured documentary states of soul. Something unpredetermined at the heart of the films. I think there's something similar in your films. Your framing is very respectful. The films are powerfully emotional but your characters are almost presented to us like Bresson's models. Bresson used a lot of close ups, although rarely of faces. The daughter in Father and Daughter, especially, we never get close to her face and yet we feel so much about her.

MDdeW: I think that's true. If there are similarities between us, it's that I don't force emotions into the audience's face. And in a way, it goes against all of the rules of filmmaking. Definitely in animation, the veterans always talk about emotion. Make it stronger. Make it clearer. Make it powerful. In animation, you can't easily be subtle with emotions, so you show one emotion at a time, or maybe a conflict of two emotions at the most. And you make it very explicit. Bresson was different. He made emotional films but without forcing emotions upon us that way. I knew Father and Daughter would be a film with a lot of feeling but with no direct emotion from the characters' faces or voices. It would be in the whole context and body language, composition and narrative. And in the film's stillness and emptiness. That was my challenge but also my natural taste. Something I wanted to do and would do again. And the monk, too, is emotional in his body language but you never see a close up of his face. For the same reason. I felt that the totality of the image was enough to express all of this.

JH: Spoken like a true Bressonian! I was looking for similarities and in addition to the interest in painting, "une ecriture", simplicity and directness, I also found this documentary sincerity and respect. But that's strange for animation, where everything is intentional. It arises from allowing us to observe and make our own connections and conclusions. I think that corresponds to Bresson, on one hand the least documentary of fiction filmmakers but at a deeper level, absolutely committed to a form of documentary.

MDdeW: Yes, and in my last two films I included close ups of birds, trees, clouds and other details from nature. That's something documentaries tend to do. I can't say I chose a particular documentary style, but I was aware of these choices.

JH I have one specific question. The daughter, there's something extraordinary that occurs with her physiognomy. She starts with a definite human face at a distance and then she becomes a recognisable girl and has a girlish form and then, as an old woman, she's almost dehumanised. She's like a character from Maus. A little, fragile, elongated figure. What was happening there?

MDdeW: That happened unintentionally. I was designing the different stages of her character's development but afterwards I felt that there was a discontinuity between the realistic and the less realistic but it didn't bother me.

JH: It's so powerful.

MDdeW: Incidentally, I'd love to make a whole film just with old people. I loved drawing that little old lady, although I had to redo a very long scene where her bicycle keeps dropping. It's a pleasure to animate. It's a nice character. And she has such a characteristic look and behaviour.

MDdeW: Yes, there's certainly a similarity there and also in the use of close ups. Of shoes walking, of hands, or a door which is about to open. I suspect that, if Bresson had gone to an animation festival, he'd have found many other films he'd have liked. The films are very individualistic, like poems. And that attracted me when I first went to an animation festival as a student, the Annecy Festival in the mid-seventies. I looked at the films and responded to this amazing display of different worlds. And filmmakers, too, are mostly modest and discrete. They're hard working. They're often well travelled, broad- minded and very dedicated. "That's the film — go and see the film". The maker's face is not important. And I thought, "This is my world. I want to be part of this". And since it's not lucrative to make personal films, there is a genuine atmosphere, with respect and sympathy for the filmmakers.

JH: Would you like to make feature length films?

MDdeW: I've been asked. I don't have an easy answer. Part of me thinks that'd be wonderful. But also, I could only do it by taking 4 or 5 years of my life. I could only do it if I felt totally passionate and I don't have a subject yet. I have some ideas but not that complete obsession. The other thing is, I look at some colleagues; you can make such films without compromise but it is very hard. There's always the interference of the investors. You have to be very tough and that's perhaps not my approach. I would need a lot of vision and support, not to succumb to all of these pressures. In short, I don't know, but I don't exclude the possibility of making longer films.

JH: And why Muswell Hill? Is that because of the commercials industry? Why not the US?

MDdeW: Or maybe France, where the feature animation industry is active. London is a good place for independent animation. I can survive by doing commercials, children's books and teaching and a lot of people who make their own films are in, or near, London. And especially in the 70's and 80's - but still now - there is a compatibility between making commercials and making your own shorts. There are quite a few people like me who do both.

JH: Commercials pay the bills but also allow you to experiment and extend your practice.

MDdeW: Exactly. And to push your own limits. Every time I do a commercial I try something new in technique, drawing style and narrative. You think "this is going to be impossible" and afterwards, after you have pushed yourself, you have improved your style. You just can't make money from your own short films. On the contrary, you end up putting your own money into them. But for me there's not a conflict between commercials and personal films because I felt I had to strengthen my own skills and widen them. In the British commercials industry there are some exquisite films and I'm proud of some of my commercials. So, I've no problem with doing them. Nowadays, of course, there's much more of a mixture between live action and special effects. In the 70's and 80's, it was pure animation, based on a book illustration style, or a painterly style. Now, it's more slick and realistic, which can also look very beautiful and be very skilful work. In features as well. But that's not entirely my field. I prefer to keep illustrating, rather than doing it by computer.

|

|

JH: But technology is part of the process?

MDdeW: Yes, I work with computers during the second stage. My first stage is still drawing but then I scan the images into a computer. On Father and Daughter, for instance, lots of backgrounds were worked on in Photoshop. Everything was done in black and white to start with, using pencil and charcoal and then I coloured everything digitally, for practical reasons, so I'm delighted with computers. Quite a few of my colleagues have recycled themselves into full time computer animators, Shrek or Toy Story style.

JH: Will young animators lose the skills of traditional animation?

MDdeW: No, I don't think so. There will always be those who pick up a pencil or a brush, I'm sure and there will always be an audience because it's too beautiful and too rich to forget. I draw a parallel with music, where electronic and digital instruments and tools have created endless possibilities, yet acoustic instruments have not lost their popularity. And a blend between the two can also be very beautiful. It's just the same with animation. Hand drawn animation will remain loved and will continue to evolve, while computer animation will generate fantastic new stuff.

JH: Live action and animation are converging with the advance of digital technology. It's just that the need to create original or engaging stories will persist. As always, technology brings both risks and opportunities.

MDdeW: Live action and animation have definitely become much closer. But both bad taste and inventiveness continue. And I occasionally meet people who are surprised when I say that I still draw and who think that computers do it all. I have to remind them that computers are only a tool. To give something soul, or to make it really moving in an interesting way, you're back to being an animator, just using computers as tools.

JH: Yes, the central questions, those that go beyond technology and technique, remain the same. Michael, thank you for talking about your work, especially in the light of being awarded the Prix Robert Bresson and for addressing the interesting questions and comparisons that have arisen this afternoon.

[JEH: 1.ii.2005/2]

Michael Dudok de Wit's Academy Award-winning Father and Daughter is available on region-free PAL DVD via www.animationwebshop.nl. For PAL or NTSC VHS copies contact Ursula at the Netherlands Institute for Animation Film,

Attn: Ursula van den Heuvel, Postbus 9358, 5000 HJ Tilburg, Holland. Tel +31-13-5324070, heuvel@niaf.nl.

The Monk and the Fish (Le Moine et le Poisson) can be ordered directly from the studio where

it was produced: Folimage in Valence, France, folimage@wanadoo.fr,

Fax +33-4-75430692.

Some Dudok de Wit demo reels (QuickTime) are found here.